The Grateful Dead Live is not a nostalgia project. It is not a museum. It is not a greatest-hits channel or a tidy playlist wrapped in classic rock radio formatting. It is living, breathing, evolving audio history — a place where every song you hear is alive, stretched, reimagined, and delivered the way the Grateful Dead always intended it to be experienced: in motion, in community, in the moment. And today, the entire live universe feels quieter.

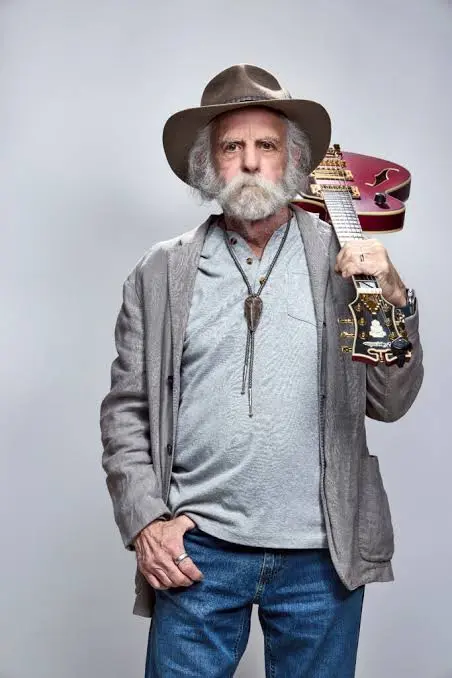

Bob Weir has passed. And the world did not just lose a guitarist. It lost one of the last true architects of modern live music culture.

Bob was not merely a founding member of the Grateful Dead. He was a rhythmic engineer of feeling, a storyteller with a six-string, a cultural conduit who helped turn concerts into pilgrimages and songs into shared languages. For more than six decades, he never stopped stepping onto stages, never stopped chasing connection, never stopped building community through sound. He lived inside the live experience — and now lives inside it forever.

For some of us, Bob was more than a legend. He was real. Present. Human. Probably the first so-called “man crush” I ever had in my life. I had the privilege of meeting him and being in his presence many times socially — not as a headline, not as a framed photograph, but as a person. We spoke for hours one night, casually, honestly, and without agenda. We crossed paths socially many times. He stepped on my foot once, and somehow that became one of my favorite stories to tell. He called me his “little buddy” apologizing for him stepping on my feet while I was in his way (he was headed to the bathroom from the stage) mind you that night. I loved it. I said to step on my feet anytime dude.

I met him again at the Wiltern Theatre during a record release event that turned into one of the most perfectly and unique moments imaginable — a power outage that transformed a polished industry function into an impromptu acoustic sing-along. Bob performed while the lights were dead and with no power. Suits and record executives — the same people who usually watched charts and margins — were suddenly singing along to “Truckin’,” voices unguarded, grinning like teenagers. That was Bob. He dissolved walls just by showing up with a guitar.

At one of the very earliest Bobby & The Midnites shows — at the tiny Brandywine Club right on the Pennsylvania-Delaware line — Bob literally stepped off the stage and onto our dinner table to play directly to the corwd whikle I stared up at him being inches from my face. The room was barely larger than a living room. I wonder if he ever played on a table before or after that night and honestly, as odd as it seemed for him, it worked for me at least.

And then there was Bill Graham’s pool water slide deck — where a casual conversation drifted into stories about songs, first shows, and, strangely enough, a rogue coyote that had been preying on pets in the hills he said he wanted to shoot with his rifle. The moment was surreal, funny, philosophical, and deeply human — the kind of memory that lives in your bones, not your calendar.

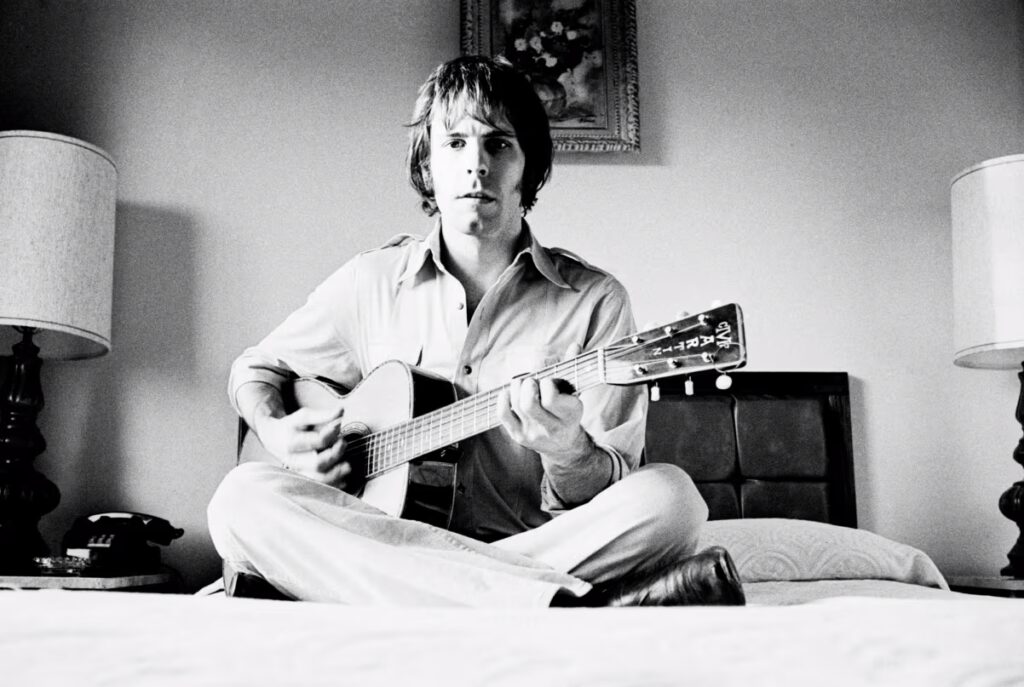

Bob Weir was the youngest member of the Dead when he joined as a teenager in the early 1960s, nicknamed “the kid.” Alongside Jerry Garcia, he helped form the foundation of a band that would become a movement. They were pillars of the Haight-Ashbury counterculture, architects of the Acid Tests, pioneers of psychedelic improvisation, and builders of one of the most fiercely loyal fan communities music has ever known.

He wrote and co-wrote songs that are now cultural scriptures — “Sugar Magnolia,” “Cassidy,” “Throwing Stones,” “Truckin’,” and countless others — songs that do not age, but instead evolve every time they are played. The Dead allowed fans to tape their shows, encouraging trading and sharing long before streaming ever existed. They built the legendary Wall of Sound. They performed at Woodstock. They drew more than 100,000 people to Englishtown, New Jersey. They changed what a concert could be.

And through all of it, Bob Weir remained anchored to the live experience. I used to marvel at his playing as a kid because he never played traditional lead guitar licks, which for me was completely new in the 1970s and early 1980s—especially at that level of musicianship. What made it even more remarkable was how he intermingled his strumming and chord voicings with the entire band. It was honestly the most pivotal element in keeping a group built on 100 percent improvisation coherent and elevated.

Without Bob and his style of playing, the band would not have reached that higher plane. Everything was layered on his foundation—his rhythmic architecture created the swirl, the motion, and the living framework that everything else was built upon and revolved around. That sense of circular movement, of sound constantly folding back into itself, began with Bob.

At the time, his style was entirely new to me, and I was what you might have called a “Bob Deadhead,” because the camp really was split back then. The first songs I gravitated toward as a kid were from Go to Heaven. I was looked at like a lightweight or a Go to Heaven Deadhead, but I loved “Saint of Circumstance” and “Alabama Getaway.”

The first time I ever truly paid attention to a Grateful Dead song was when I saw them on Saturday Night Live. “Alabama Getaway” struck me immediately—it felt oddly structured and different from anything I had heard before. Later in the show, when Bob came out wearing bunny ears and they played “Saint of Circumstance,” something clicked. When they hit the crescendo at the end — “Sure don’t know what I’m gonna do” — I remember thinking, this is a cool song. I went out and bought the album, and that same year I saw them live for the first time in November of 1979.

I went on to see hundreds of shows before Jerry Garcia passed away in 1995.

Even after Jerry Garcia’s passing, Bob kept the flame alive — rebuilding, reshaping, and finally launching Dead & Company with John Mayer, introducing the Dead’s language to new generations and filling stadiums and arenas once again. As recently as this past summer, he was still on stage, still carrying the sound forward, even while quietly battling cancer and underlying lung issues.

The Grateful Dead Live radio universe exists for artists like Bob. It exists because live music is not a recording — it is a living event. It exists because Deadheads understand that no two nights were ever the same, that every performance was a conversation, that every song was an open road.

And here, on The Grateful Dead Live, Bob Weir will never stop touring.

His voice will still rise during “Sugar Magnolia.” His guitar will still weave through “Truckin’.” His rhythms will still bend time during late-night jams that drift between worlds. He is still here — in the live ether, in the endless tapes, in the songs that never truly end.

We lost a man.

But the music never stops.

Bob Weir is now eternal — not frozen in history, but forever moving forward, one live song at a time.